In most puzzle games, the narrative purpose of solving puzzle is far grander than the puzzle itself. You need to draw lines through the mazes in The Witness in order to unlock the secrets inside the mountain, in Portal you are trying to escape a dilapidated testing center, and in The Talos Principle the protagonist is proving themselves to be worthy of replacing humanity. In Stephen’s Sausage Roll, you are Stephen (presumably) and you cook sausages. You aren’t saving the world through your intelligent heroics, you are purely cooking a copious amount of sausages that are each twice as large as you are.

The inherent silliness of Stephen’s Sausage Roll’s premise is hilariously juxtaposed with the player’s experience of the game, which is decidedly demanding. I have occasionally found it difficult in my life to cook a sausage – because no matter what you put the heat at on the stove, the damn thing never wants to cook all the way through – but I have never been so perplexed about how best to cook a sausage before playing Sausage Roll. In the game, you don’t fail by undercooking the center, but you fail in every other conceivable way: you can overcook the sausage, knock it into the ocean, have the sausages block your escape from the level, have one sausage block another’s passage, move it to a corner where it’s out of your reach, get it stuck on your fork…the list goes on. All of these ways to fail are from deceptively simple levels.

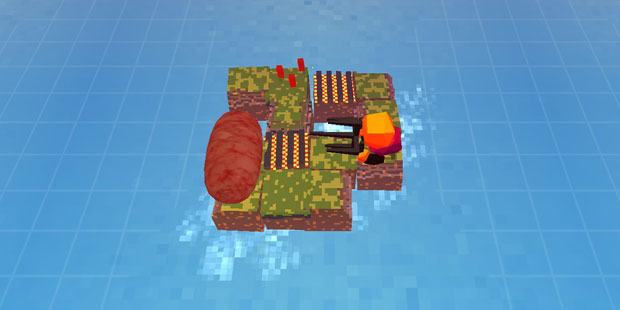

Look at this shit, there is only 1 sausage, 2 grills, and 7 tiles for the player to step on. This should be easy! So why do I keep overcooking one side of it or pushing it out of reach? As I’ve learned, it’s because the game’s power over the player is its simplicity.

French social theorist Michel Foucault described a modern type of power, which he called disciplinary power. Instead of old world forms of power, where you torture criminals on the streets as an example for all to see, disciplinary power regulates the behavior and movement of the individual to control them. You can see this playing out in schools where children are told where to sit, how to stand in line, where they can play tag, etc. This type of power restricts the individual’s ability to make choices of how to behave, when they can act on their own, and where they can go.

This philosophy is evident in video games as well, but many games are enjoyable because they give players the control. Games that want to empower their players give them a myriad of ways to control their character’s behavior and movement, thus relinquishing the game’s disciplinary power over them. In Grand Theft Auto V, players can run, shoot, swim, drive any car, pilot boats and jet skis, fly fighter jets and helicopters, call gang members to assist them, buy clothes, perform heists, have sex…the list goes on. Many of these actions are unavailable, restricted, or illegal (for good reason) in actual society and that’s why it’s so empowering to live out those fantasies virtually. The simple act of running red lights in GTA is satisfying because it allows the player to fictitiously conquer the disciplinary powers that they constantly encounter in everyday life.

Stephen’s Sausage Roll is the antithesis of GTA in this way. Where many games make superhuman tasks easy to accomplish, Sausage Roll makes the quotidian task of cooking sausages nearly impossible. It seeks to disempower the player by heightening Foucault’s idea of disciplinary power. The power the game has over you comes from hyper restricting the player’s behavior and from the limited organization of the play space. The only direct interaction the player has control over is to walk in four directions. The already restricted behavior is further limited by the big grill fork that you have in front of you at all times. At the beginning stages of this game, learning to deal with the fork made me relive memories of being a gangly 15 year old stumbling around with my newly sprouted long legs. I could never get anything quite right, always turning towards a sausage that I wanted to push, but the swing of my fork accidently bats the sausage into the unanticipated direction of the ocean below, causing me to fail the level.

The difficulty of navigating the world with a protruding unwieldy fork is amplified by how little room there is to navigate. What appears to be simplicity of the level is, in actuality, restrictive. The interplay between limited movement and limited space for movement amplifies disciplinary power, making the seemingly simple task of cooking a sausage into a source of consistent failure.

You have to crack a few eggs to make an omelette, and you have to burn a few Stephens to cook a sausage. Such is the nature of life according to Stephen’s Sausage Roll.

Written by Taylor Kalsey, who was bored and home for the holidays

Transit designers have to account for the unpredictable, anyone must be able to go anywhere, including places that don’t exist yet. As the designer in Mini Metro, you must keep all train-lines impossibly flexible, so no matter where and how your city grows, your design can always adjust maintain balancing a thousand plates at once. Well, at least that’s how I’ve been playing it.

Transit designers have to account for the unpredictable, anyone must be able to go anywhere, including places that don’t exist yet. As the designer in Mini Metro, you must keep all train-lines impossibly flexible, so no matter where and how your city grows, your design can always adjust maintain balancing a thousand plates at once. Well, at least that’s how I’ve been playing it.